An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.  An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know. Unit:

101st Airborne Division, 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment

Date of Birth:

October 12, 2017

Hometown:

Breckenridge, Colorado

Date of Death:

June 9, 1944

Place of Death:

Carquebut, Normandy

Awards:

Purple Heart

Cemetery:

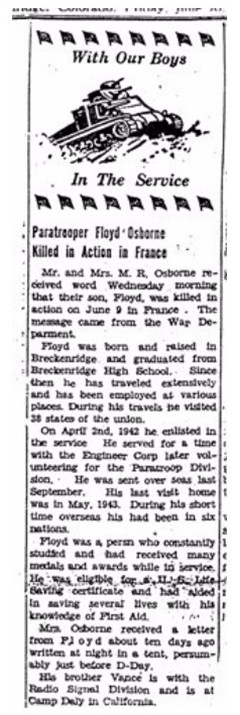

Floyd Osborne grew up in the mining town of Breckenridge, Colorado, with his parents and four siblings. His father, Malcom, worked as a miner and his mother, Marguerite, owned a drugstore and worked as the local pharmacist. His siblings, Claire and Jerry, preceded him in death and his brother, Vance, and sister, Marguerite, survived him. Vance also served during World War II in the Radio Signal Division.

As a teenager, Floyd Osborne attended Breckenridge High School where he played basketball. After high school, he traveled extensively throughout the United States and settled in Miami, Arizona, where he enlisted on April 3, 1942.

Before settling in Miami, Arizona, Osborne lived in Breckenridge, Colorado. His family were miners, and he worked in this industry before enlisting. Dredge mining for gold was popular in Breckenridge during the 1940s. When World War II started, Breckenridge residents were recovering from the Great Depression. By October 15, 1942, the War Production Board ordered all gold mining to stop. They diverted manpower, metal, and machinery for wartime use.

The Miami Copper Company was the largest mining company in Miami, Arizona, during World War II. The mine supplied copper ore to make wire and cables. The mining companies in Miami doubled their efforts in 1942 with government funding under the direction of Governor Osborn. The governor secured federal subsidies and raised the price of copper at least 15 cents per pound. The bombing of Pearl Harbor prompted Arizona mines to work 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Also in Arizona, B-24 bombers were built for the war. Several new air bases were added, giving birth to Arizona’s aviation and manufacturing industries. In Phoenix, citizens adjusted their daily lives and aided the war effort by recycling, organizing bond drives, and assisting soldiers. Miners, farmers, and defense workers labored to provide materials that were necessary to win the war. Arizona was also home to two of the larger Japanese internment camps, the Gila River War Relocation Center and the Colorado River Relocation Center.

The 101st Airborne Division was activated on August 16, 1942, at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana. The division included the 327th and the 401st Glider Infantry Regiments, and the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR). The 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment was stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia. Later the division added the 501st and 506th Parachute Infantry Regiments. Major General William C. Lee, referring to the 101st Airborne Division’s lack of combat experience, said that the Division had a “rendezvous with destiny.”

The division moved to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, in October 1942 to train these soldiers for their missions. To qualify as a paratrooper, soldiers who volunteered for this dangerous job needed to complete five jumps. As the men trained, an intense rivalry between glidermen and paratroopers developed. Adding fuel to the rivalry, paratroopers received extra money ($50 per jump) due to the dangerous aspect of their missions, even though the glidermen had equally dangerous missions. Paratroopers also wore a special uniform and shiny jump boots.

In 1943, the division left North Carolina to take part in the Tennessee maneuvers. They later returned to Fort Bragg and received their orders to go overseas in mid-August. After arriving in England, the 101st Airborne Division stayed in Wiltshire and Berkshire and continued to train until they were deployed for service.

While in England, the 101st Airborne Division participated in three formal training exercises: Beaver, Tiger, and Eagle. In both Exercise Beaver and Exercise Tiger, the 101st Airborne Division practiced jumping from trucks, instead of planes, and simulated the capture of causeway bridges that crossed the estuary behind the beach. During Exercise Eagle, the troops jumped from airplanes and again simulated the capture of causeway bridges. Even though some jumped at the wrong coordinates due to a misunderstanding, the exercise was considered a success.

The 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment was ordered to jump behind enemy lines in Normandy, France, to secure two northern causeways that led inland from Utah Beach and destroy a German battery of four 122mm howitzers near Saint-Martin-de-Varreville, France.

Many of the paratroopers missed their intended drop sites. The Pathfinder teams could not activate their amber holophane lights or Eureka beacon until the drop was in progress. The incoming planes faced heavy enemy fire. The paratroopers found themselves far from their original drop zones. The men struggled to locate each other at night in the middle of enemy territory. Eventually, many of the troops reunited with others and played a critical role in securing the causeways leading away from the beach.

Prior to volunteering to be a paratrooper, Osborne served in the Engineer Corps. He trained at Camp Roberts, California. He volunteered to join the 101st Airborne Division and became a member of the Regimental Headquarters Company, 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment. Osborne jumped into Normandy as a demolition specialist. Most of his unit landed near Saint-Martin-de-Varreville. At some point, Osborne suffered a gunshot wound to the chest, and succumbed to his wound on June 9, 1944.

He was originally buried in Saint-Mère-Église (Temporary Cemetery #1) and his mother was notified of his death on June 28, 1944. She decided to bury him in France permanently. In 1948, his remains were moved one final time to the Normandy American Cemetery.

.jpg)

“United in this determination and with unshakeable faith in the cause for which we fight, we will, with God’s help, go forward to our greatest victory.” General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Floyd Osborne was born on October 12, 1917, in Breckenridge, Colorado. His parents were Malcom and Marguerite Osborne and he had four siblings. When Floyd was in high school he played basketball and had a deep respect for the law. Floyd never married, and was 26 years old when he died.

Floyd lived in Miami, Arizona, for a year when he decided to enlist in the Army on April 3, 1942. He volunteered to become a paratrooper, and was with the 101st Airborne and 502nd Parachute Regiment. It was very brave of him to become a paratrooper because it was so dangerous and it was untested in warfare. Floyd made the jump on D-Day with his fellow paratroopers. On June 9, 1944, Osborne’s unit was fighting near the small town of Carquebut. Osborne suffered a fatal gunshot wound to the chest and passed away on the same day. One of Floyd’s friends who was a member of the same platoon said, “I regarded him as one of the finest men I have ever worked with. His conduct on the field of battle was outstanding.” Floyd was someone that others could depend on when they needed him and he received a Purple Heart for his service.

Floyd Osborne sacrificed his life so we and our Allies could be free. Floyd’s story was once silent, but there is now a voice and story attached to him. Thank you Floyd for your willingness to fight to protect our freedoms, thank you for aiding our Allies, and thank you Floyd and the thousands of other men for making the ultimate sacrifice for our country.

Arizona. Gila County. 1940 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Colorado. Summit County. 1920 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Colorado. Summit County. 1930 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Larkin, T.B. Letter to Mr. Malcolm R. Osborne regarding Floyd Osborne’s internment in France. October 24, 1946.

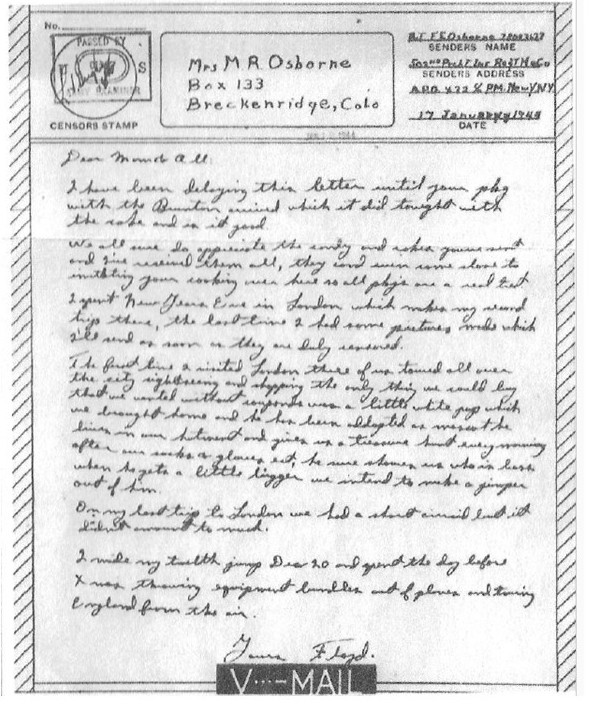

Osborne, Floyd. Letter to Marguerite Osborne and family regarding his time in England. January 17, 1944.

Personal Collection of Marilyn Sheesly. Floyd E. Osbornes’ Birth Certificate. October 12, 1917.

Personal Collection of Marilyn Sheesly. Floyd E. Osborne’s First Day of School Photograph.

Personal Collection of Marilyn Sheesly. Floyd E. Osborne Military Photograph.

Personal Collection of Marilyn Sheesly. Obituary of Floyd Osborne. Breckenridge, Colorado. 1944.

Personal Collection of Marilyn Sheesly. Western Union. Telegram to the Osborne family regarding their son’s death. June 28, 1944.

Records for Floyd Osborne; World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946 [Electronic File], Record Group 64; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Roderick, Charles R. Personal letter to Mrs. Marguerite C. Osborne offering assistance with the death of her son. July 1, 1944.

Ulio, J.A.. Letter to Mrs. Marguerite C. Osborne regarding the confirmation of a previously sent telegram. June 27, 1944.

101st Airborne Division (AASLT) Public Affairs Office. “Welcome to the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault)”. U.S. Army. Last updated on August 20, 2012, accessed February 23, 2017. www.army.mil/article/85879/.

“101st Airborne Division.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Last modified May 8, 2014, accessed August 5, 2014. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/101st_Airborne_Division.

“The 101st Airborne During World War II.” The 101st Airborne Division Website. Accessed February 23, 2017. www.ww2-airborne.us/18corps/101abn/101_overview.html.

“American Battle Monuments Commission: The World War II Honor Roll.” American Battle Monuments Commission. Accessed February 26, 2014. www.abmc.gov/node/412208#.WLb-UYgrI1I.

Arizona Goes to War: The Home Front and the Front Lines during World War II. Tucson: U of Arizona, 2003. Print.

Gilliland, Mary Ellen. Breckenridge: 150 Years of Golden History. Silverthorne, CO: Alpenrose, 2009. Print. (book).

Gilliland, Mary Ellen. Summit: A Gold Rush History of Summit County, Colorado. 25th ed. Silverthorne, CO: Alpenrose, 1980. Print. Anniversary Edition. (book).

Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army. 1988. Information from the Hospital Admission Cards Created by the Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army (1942-1945) and (1950-1954) Information for the Year 1944. National Personnel Records Center by the National Research Council.

“Pathfinder.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Last modified July 27, 2014, accessed August 6, 2014. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pathfinder_(military).

Sheesly, Marilyn. Letter to Amy Braun regarding her uncle Floyd Osborne. 2014.

Sheesly, Marilyn. Telephone interview with Amy Braun. March 14, 2014.

Soss, C., Tiede, Marlene, and Hayward, Delvan. Around Miami. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2011.

The American Battle Monuments Commission operates and maintains 26 cemeteries and 31 federal memorials, monuments and commemorative plaques in 17 countries throughout the world, including the United States.

Since March 4, 1923, the ABMC’s sacred mission remains to honor the service, achievements, and sacrifice of more than 200,000 U.S. service members buried and memorialized at our sites.