An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.  An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know. Unit:

66th Infantry Division, 262nd Infantry Regiment

Date of Birth:

February 20, 2020

Hometown:

Chicago, Illinois

Date of Death:

December 25, 1944

Place of Death:

English Channel

Awards:

Purple Heart

Cemetery:

Andrew Deamantopulos was raised on the North side of Chicago, in the diverse neighborhood of Avondale. His parents were immigrants from Greece. His father, Nick, was a soldier in World War I, and his mother, Katherine, was the mother of eight children: Andrew, John, Mary, Francis, Peter, Angelo, Micke, and William.

Andrew’s brother, John, served in the the Air Corps during World War II. John was similar to his brother. They both attended Carl H. Schurz High School, both joined the Senior Boys club, and both worked as part time waiters. Before the war, Andrew found his passion in the arts. He worked as a part-time actor, and he attended college.

The Deamantopulos family, like many immigrant families, decided to settle in an urban city: Chicago. After years of economic depression, the city began mobilizing for war. In the months after Pearl Harbor, Chicago witnessed a growth of industry and an increase of patriotism in its neighborhoods.

Nuclear research was conducted in 1942 at the metallurgical laboratory of the University of Chicago. This research contributed to the construction of the atomic bombs. In addition, high schools and local communities started parades dedicated to the war effort. High schools also started clubs that were heavily influenced by the military. In Carl H. Schurz High School, the Officer’s Club, ROTC, and the Rifle Team were very popular clubs at the time.

The war effort was not only focused on men. Propaganda targeted women to join factories building weapons for the war. Posters all over Illinois encouraged women to become nurses. The push for the mobilization of women also appeared in newspapers. The Chicago Tribune included stories of women joining the war effort by becoming nurses. One article, “World War I. Nurse Busy in World War II” told the story of Mrs. Fallbacher, a very busy nurse. She attended 300 people per week, and it seems her work is never completed. The article offers insight on the busy schedule of Chicago nurses. The Chicago Tribune and other newspapers at this time wrote articles on the war, which showed the patriotism in Chicago.

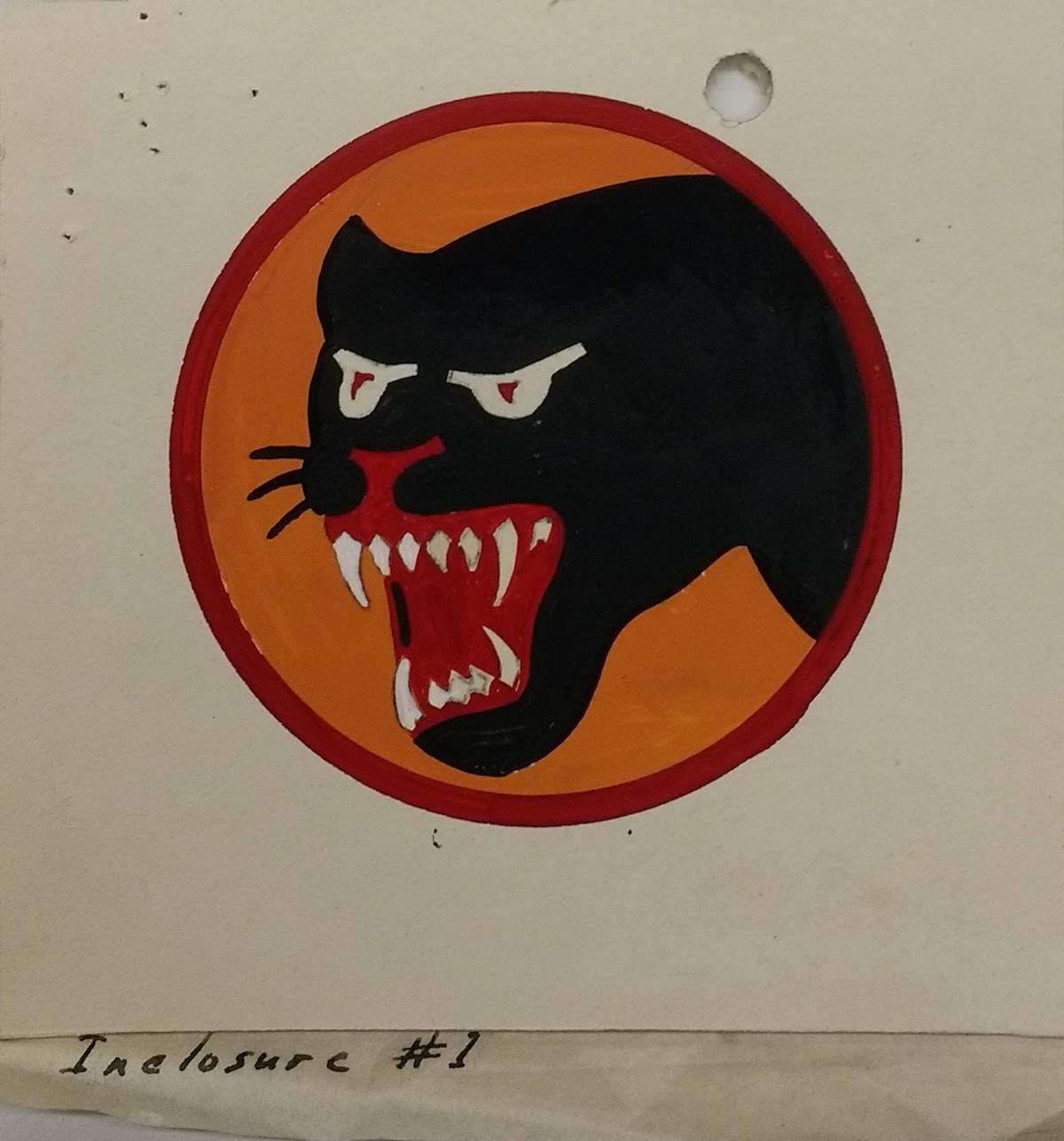

Private First Class Deamantopulos was drafted in 1942, and began his military journey at Camp Blanding, Florida with the 66th Infantry Division. The panther was the division’s mascot and therefore the soldiers called themselves panthermen. Deamantopulos served under the command of Major General H. F. Kramer. The division trained at Camp Blanding until April 15, 1943. Deamantopulos and his fellow soldiers then transferred to Camp Robinson, Arkansas. The division moved for a third time and completed their training at Camp Rucker, Alabama. Finally, the division was ready for combat.

The 66th Division was shipped overseas on November 26, 1944. They landed in Dorchester, England on November 12, 1941. At Dorchester, the 66th Infantry Division trained and prepared for debarkment until December 24, 1944, then they transferred to Southampton. The 66th Division’s final destination was the French city of Cherbourg. Their goal was to contain and eliminate the remaining pockets of German soldiers in Northern France. Deamantopulos never reached Cherbourg.

Private First Class Deamantopulos never got the chance to put his training to use, nor did he return to Chicago. On December 24, 1944, Private First Class Deamantopulos left England on a troop carrier ship, the Leopoldville. Its destination was the French city of Cherbourg, but German U-Boats halted the 66th Infantry Division’s advance. Deamantopulos and his fellow soldiers were 5.5 miles away from Cherbourg when a torpedo struck the Leopoldville.

The torpedo hit the compartment in which the 262nd Infantry Regiment was quartered. Only 19 soldiers of 262nd Infantry Regiment survived the hit. The 66th Infantry Division lost 14 officers, including two battalion commanders, and 784 enlisted men. Among the 784 soldiers, was Private First Class Deamantopulos.

There are several accounts of the ship going down that communicate the fear and horror that soldiers must have felt that night. Sergeant Cornelius P. Burk of 264th Infantry Regiment, Company E, explained how he was simply playing the harmonica when “something hit. It seemed to be in the compartment below us. It throwed [sic] everybody off…”

After the wreck, the ship’s crew and the soldiers were both equally confused as to what had happened. The soldiers were “waiting for the signal to abandon ship” but it never came. Many soldiers blame the Leopoldville crew for some loss of life. According to the soldiers, the crew was Belgian and could not speak English proficiently. As a result, there were communication problems between the passengers and the crew. If the captain did give the order to abandon ship, the soldiers of the 66th Infantry Division never heard it.

Before Private First Class Deamantopulos became a soldier he was Andrew Deamantopulos. He was from a large family of Greek immigrants. Private First Class Deamantopulos and his family called the northwest side of Chicago home. He grew up in the calm, pleasant, and diverse neighborhood of Avondale.

He attended Carl Schurz High School, a typical Chicago public high school, with a large beautiful building. Private Deamantopulos was not very tall; he might have gotten lost in the student crowd at one point. After high school, Private Deamantopulos was a waiter and a part time actor. It must have been a shock when he realized he could no longer act, but must be sent off to war to defend democracy. He was put under the command of the 66th Infantry Division, 262nd Infantry Regiment. The 66th Infantry Division would travel the Atlantic Ocean and take up camp in England.

Private First Class Deamantopulos was not part of the initial invasion that stormed into Normandy, instead he and his fellow soldiers were supposed to be reinforcements for the Battle of the Bulge. He would never see combat, as he died along with 784 soldiers in the English Channel after a German U-Boat torpedoed the Leopoldville.

Private Deamantopulos made the ultimate sacrifice for his country, city, and family. He was not the traditional soldier: he did not understand military culture in high school, he was not athletic, and he did not see combat. It is easy for Private First Class Deamantopulos’ name and legacy to be lost in the archives because at first glance he seems irrelevant. I argue that he might not have won the war, but the sacrifice he made must be recognized and honored. Few will ever make the sacrifice Private First Class Deamantopulos has made, and for that he cannot be forgotten but remembered with respect.

66th Infantry Division; World War II Operations Reports, 1940-48, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, Record Group 407 (Box 9579); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

66th Infantry Division; World War II Operations Reports, 1940-48, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, Record Group 407 (Box 9580); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

66th Infantry Division; World War II Operations Reports, 1940-48, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, Record Group 407 (Box 9592); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Andrew Deamantopulos, Individual Deceased Personnel File, Department of the Army.

Illinois. Cook County. 1930 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Illinois. Cook County. 1940 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

This photograph is of the badge of the 66th Infantry Division. Photograph. 1944. National Archives and Records Administration. Image.

“Andrew Deamantopulos” American Battle Monuments Commission. Accessed February 1, 2017. www.abmc.gov/node/408129#.WZ85XVGGPIU

Angelo, Lenore. “66th Division.” 66th Division. Accessed August 4, 2017. www.66thinfantrydivision.org/.

“Leopoldville.” Leopoldville Troopship Disaster. Accessed August 4, 2017. leopoldville.org/.

Neill, Logan. “A ‘Leopoldville’ survivor recalls sinking on Christmas Eve 1944.” Tampa Bay Times, December 22, 2012. www.tampabay.com/news/humaninterest/a-leopoldville-survivor-recalls-sinking-on-christmas-eve-1944br-br-/1267330.

“World War I. Nurse Busy in World War II” Chicago Tribune, July 4, 1943. archives.chicagotribune.com/1943/07/04/page/81/article/world-war-i-nurse-busy-in-world-war-ii.

The American Battle Monuments Commission operates and maintains 26 cemeteries and 31 federal memorials, monuments and commemorative plaques in 17 countries throughout the world, including the United States.

Since March 4, 1923, the ABMC’s sacred mission remains to honor the service, achievements, and sacrifice of more than 200,000 U.S. service members buried and memorialized at our sites.