An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.  An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know. Unit:

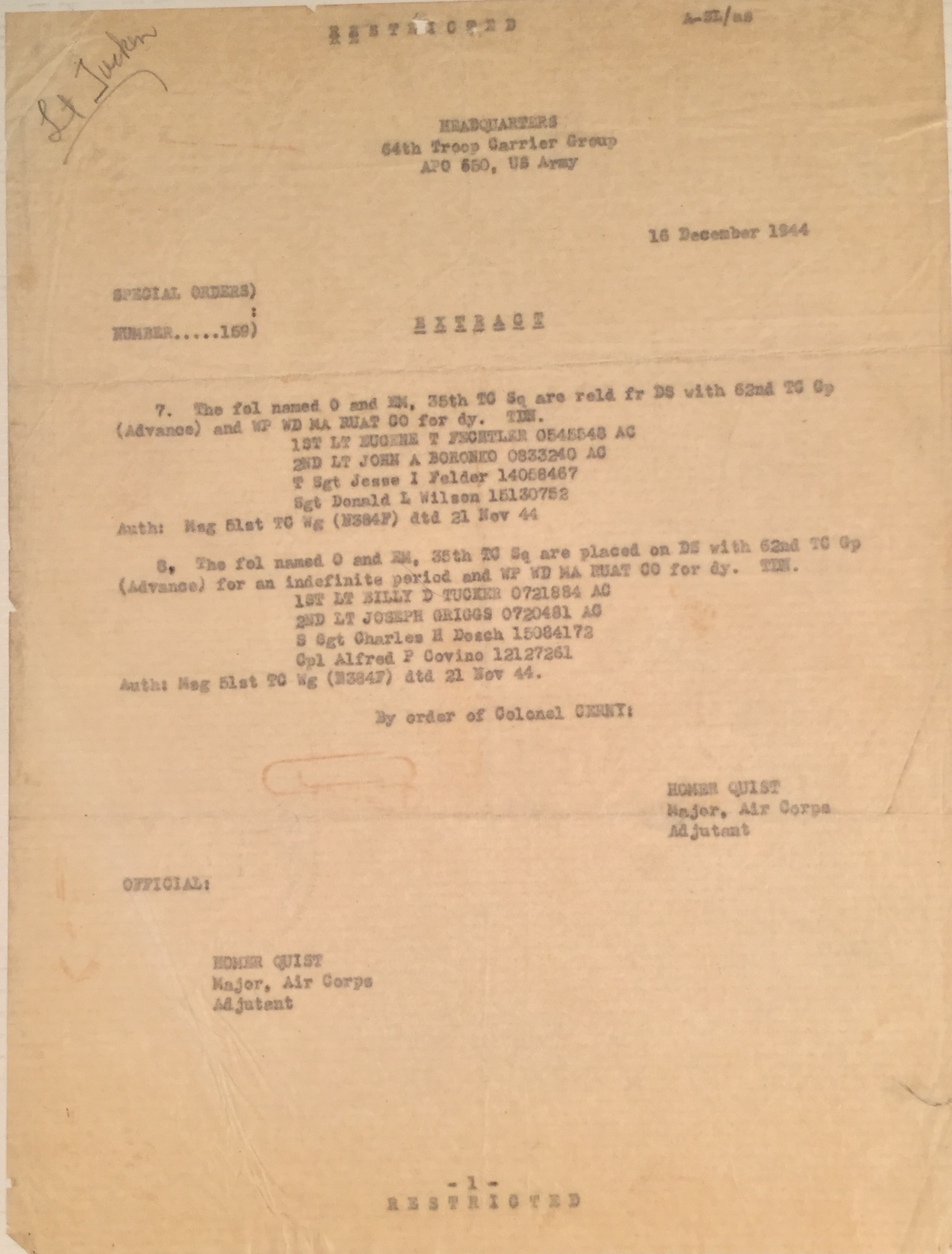

64th Troop Carrier Group, 35th Squadron

Date of Birth:

October 14, 1921

Hometown:

Jessup, Pennsylvania

Date of Death:

February 2, 1945

Place of Death:

Italy

Cemetery:

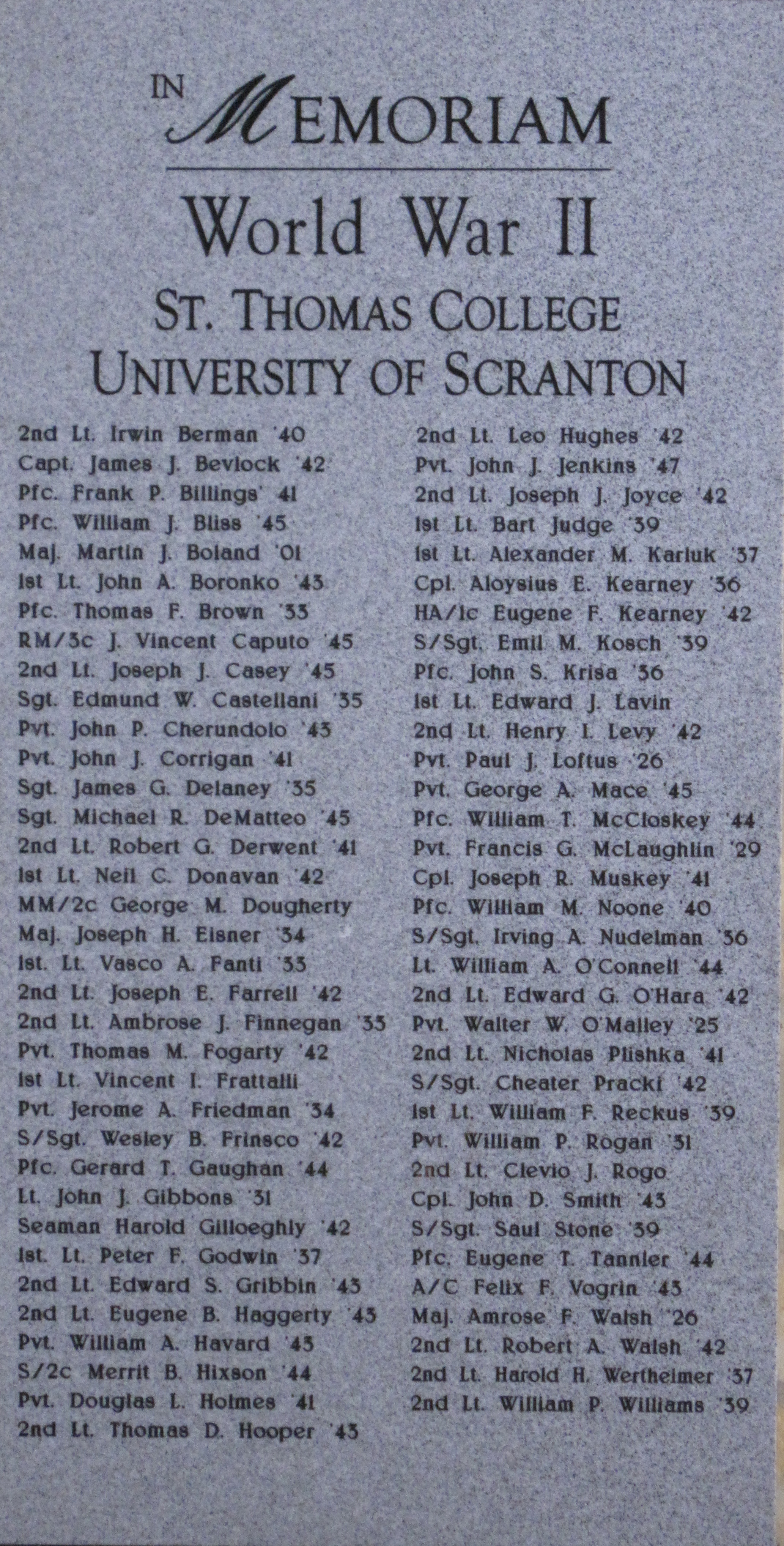

First Lieutenant John Anthony Boronko was born John Anthony Bronko. He was the oldest son of Frank Anthony Bronko and Mary Gretzula Bronko, both first-generation Americans. His grandparents came to the United States from their homes in the Austro-Hungarian Empire near the borders of present-day Slovakia and Poland.

Like other European immigrants, the Bronko and Gretzula families found work in coal country near Scranton, Pennsylvania. John Bronko lived most of his life within a few blocks of the intersection of Lane and Church Streets in Jessup. He grew up among other immigrant families from England, Italy, Ireland, Spain, Romania, and Russia. John had two younger siblings, a sister, Valeria Helen, who was called “Lil,” and a brother, Francis “Frank” Thomas.

John cherished his family’s strong ethnic ties to their central European heritage. He spoke Polish and Slovak at home. He learned the music of Slovakia and Poland and became an accomplished accordion player and instructor. He played with a band at local events. He always kept his accordion, or “hot box,” in his car just in case there was an opportunity to make music.

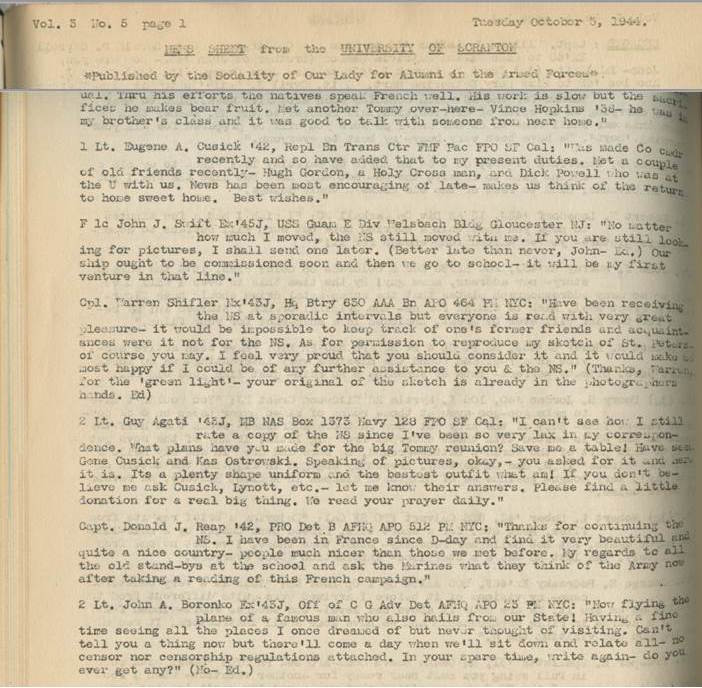

John also embraced American life. He served as captain of the basketball team and president of a singing club. After graduating from St. Patrick’s School in Olyphant, he attended night school at the University of Scranton for two semesters, earning high grades in math and French.

In 1941 John and his family moved to Newark, New Jersey. His father worked in the navy shipyards, and John worked at the Button Corporation of America. A few months later, he took a better job at Western Electric as a drill press operator making telephones, jacks, and switchboards.

In July 1942, John Anthony Bronko changed the spelling of his last name to Boronko when he was drafted into the U.S. Army. It is unclear why the spelling changed. Boronko began his military service in North Carolina.

He was always looking toward what he called his “betterment.” In November 1943, he was accepted into the Army Air Corps pilot training program at Maxwell Field, Alabama. He trained in Missouri and Tennessee before he was transferred to George Field, Illinois, where he earned his wings in spring 1944.

Boronko left for service overseas in June 1944. He arrived at Ciampino Airfield in Rome, Italy. He was assigned to the 35th Squadron, 64th Troop Carrier Group. Troop Carrier Group pilots flew the Douglas C-47 SkyTrain. Like a train on the ground, the SkyTrain moved people and supplies in the air.

In August 1944, Boronko participated in Operation Dragoon, the invasion of Southern France. Boronko’s C-47 towed a glider that delivered supplies into battle. The line of planes and gliders extended as far as the pilots could see. Once over the drop zone near Saint-Raphaël and Fréjus, the gliders released from the C-47.

Operation Dragoon connected Allied soldiers with those who landed in Normandy during Operation Overlord in June 1944. It opened what British Prime Minister Winston Churchill called the “soft underbelly” of Europe.

Boronko and his squadron moved their headquarters to Istres, France. They continued to move men and materiel across France, Italy, and North Africa. In a letter home during fall 1944, he wrote, “Having a fine time seeing all the places I once dreamed of but never thought of visiting.” A fellow squadron member, Joe Gabrosek, recalled that Boronko enjoyed a weekend pass to the beaches of the French Riviera where he was able to use the French he studied at the University of Scranton.

In December, Boronko completed a temporary assignment in Athens, Greece, to support British troops moving up the Balkan Peninsula. He flew “nickeling missions” to drop propaganda leaflets to retreating German soldiers. Boronko flew within only 100 miles of the Slovakian countryside where his grandmother had been born.

In January, Boronko moved with the rest of his squadron north to an air base near Rosignano Solvay, Italy, south of Pisa. Officers like Boronko lived in the homes of Italian families along Via Forli and Via Dante. These families rented rooms to officers in order to earn income because the shortages caused by the war were difficult.

Fellow squadron members recalled that the greatest danger they faced as pilots was not German anti-aircraft fire but the gloomy weather that fall and winter. Conditions were often foggy, and instrumental navigation was primitive. Pilots frequently navigated using the stars or following river valleys back to base. When pilots encountered a bank of clouds or fog, they were literally flying blind.

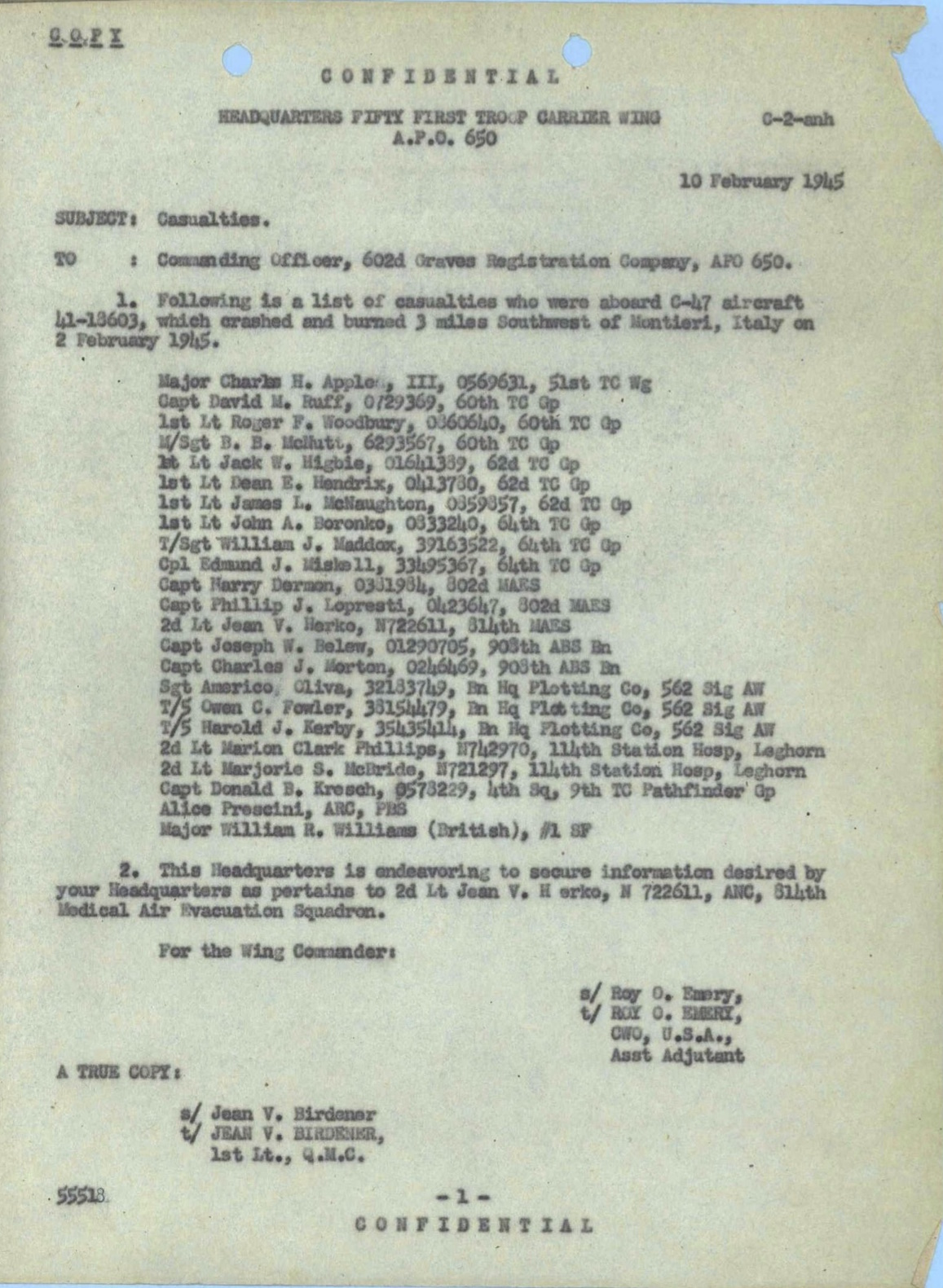

On February 2, 1945, Boronko served as co-pilot on a flight from Florence to Rome when the plane encountered heavy fog and possibly snow. The pilots tried to gain altitude, but the plane crashed into a mountain three miles from Montieri, Italy, around 10:30 a.m. The plane caught fire, and the 23 personnel on board perished. The fatalities included three U.S. Army nurses, an American Red Cross worker, a British officer, and 18 American servicemen.

Boronko’s remains, along with those of his fellow crash victims, were initially interred at the temporary U.S. military cemetery in Follonica, Italy. Due to the nature of the crash, it took several years to positively identify his body and those of the other victims. Families faced a choice to return the remains to the United States for burial or to have them reinterred at the permanent cemetery in Florence. Mary Gretzula Bronko requested that her eldest son’s body remain in Europe. On June 13, 1949, John Anthony Boronko was buried among the Tuscan hills at the Florence American Cemetery where he lies “side by side with comrades who also gave their lives for their country.”

Atkinson, Rick. The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944. New York: Picador, Henry Holt and Company, 2007.

Burton, Donna. Interview by the author. Lawrenceville Historical Society, IL. November 28, 2015.

By Day and Night We Learn to Fly. 1944. Image. Pages 16-17. Wingspan: 44D. Lawrence County Historical Society, Lawrenceville, IL.

Church Street, Jessup, Pennsylvania, c. 1930. Photograph. Lackawanna County Historical Society, Scranton, PA.

Coleson, Roger. “History of 64th Troop Carrier Group.” The Firebird Association. Last modified September 1987. Accessed December 11, 2015. www.firebirds.org/menu1/coleson1.htm/.

Gabrosek, Joseph. Telephone interview by the author. Dallas, TX. December 2015.

Gabrosek, Joseph, Jr. “Gabrosek Jr., Joseph (Interview Video) 2014.” By James Smither. Video file, 67:52. Grand Valley State University University Libraries Digital Collections Veterans History Collection. April 28, 2015. Accessed August 9, 2016. gvsu.access.preservica.com/file/sdb%3AdigitalFile%7Cc3b56605-12f6-46f6-945b-1d812a765146/.

Grave of Lt. John Anthony Boronko. Photograph. July 14, 2016.

“History of the 64th Troop Carrier Group.” Sicily-Rome American Cemetery Mobile Application. American Battle Monuments Commission.

“John A. Boronko.” American Battle Monuments Commission. Accessed April 4, 2016. abmc.gov/node/529309#.VwKPwjGrFfc/.

John Anthony Boronko, Official Military Personnel File, Department of the Air Force, Record of the U.S. Air Force Commands, Activities, and Organizations, RG 342, National Archives and Records Administration – St. Louis.

John Anthony Boronko, Individual Deceased Personnel File, Department of Army Air Corps.

Marchi, Carlo. Letter, June 1998. Collection of Bill D. Tucker.

Missing Air Crew Report; Records of the Army Air Forces, World War II (15386); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Missing Air Crew Report; Records of the Army Air Forces, World War II (16420); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

New Jersey. Essex County. U.S. City Directories 1822-1995. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Pennsylvania. Lackawanna County. 1920 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Pennsylvania. Lackawanna County. 1930 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Pennsylvania. Lackawanna County. 1940 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917-1919, 1934-1948. Digital File. ancestry.com.

Ruppenthal, Roland G. Logistical Support of the Armies. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, 1953.

Smithsonian. “Douglas C-47.” Time and Navigation. Accessed June 13, 2016. timeandnavigation.si.edu/multimedia-asset/douglas-c-47/.

Sodality of Our Lady for Alumni in the Armed Forces. “2 Lt. John A. Boronko.” INews Sheet. University of Scranton, October 3, 1944.

Tucker, Bill D. Oral History. Audio recording. 1999-2007. Collection of Bill D. Tucker Family.

Ibid. C-47 and Ambulance, Florence Airfield. December 1944. Photograph. Collection of Bill D. Tucker Family. Lubbock, TX.

Ibid. “Europe: 1943-1945.” Unpublished raw data, Collection of Bill D. Tucker Family, Lubbock, TX, n.d.

Ibid. Letter to Gabriel Milani, October 30, 2004. Collection of Gabriel Milani.

Wiltse, Charles Maurice. The Medical Department: Medical Service in the Mediterranean and Minor Theaters. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1965.

Winchester, Jim. Aircraft of World War II. Aviation Factfile. San Diego: Thunder Bay Press, 2004.

Young, Charles H. Into the Valley: The Untold Story of USAAF Troop Carrier in World War II, From North Africa Through Europe. Dallas: PrintComm, Inc., 1995.

This profile was researched and created with the Understanding Sacrifice program, sponsored by the American Battle Monuments Commission.

The American Battle Monuments Commission operates and maintains 26 cemeteries and 31 federal memorials, monuments and commemorative plaques in 17 countries throughout the world, including the United States.

Since March 4, 1923, the ABMC’s sacred mission remains to honor the service, achievements, and sacrifice of more than 200,000 U.S. service members buried and memorialized at our sites.

Invalid input. Please use only letters, numbers, apostrophes, hyphens, or periods.