An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.  An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know. Unit:

Scouting Squadron 66

Date of Birth:

September 3, 2021

Hometown:

Marshalltown, Iowa

Date of Death:

July 28, 1945

Place of Death:

off the coast of Alu Island, Mille Atoll, Marshall Islands

Awards:

Purple Heart and Navy Air Medal

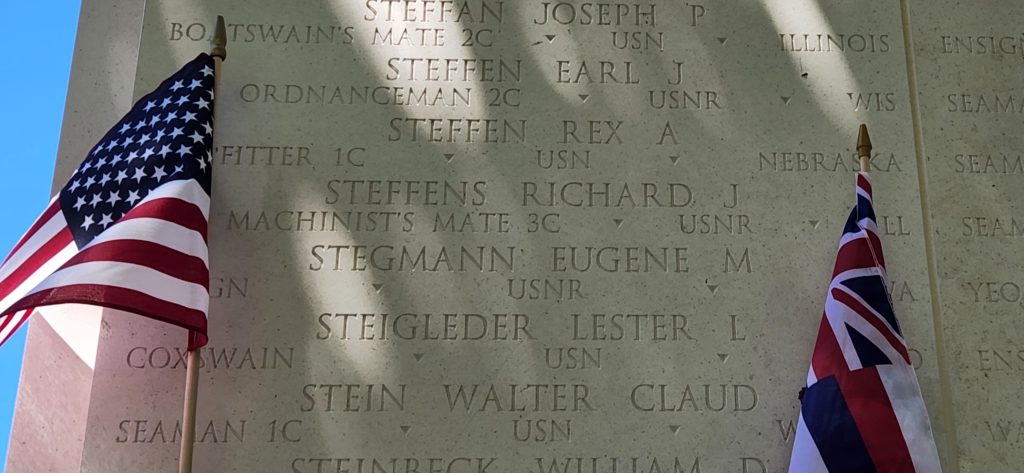

Cemetery:

Growing Up

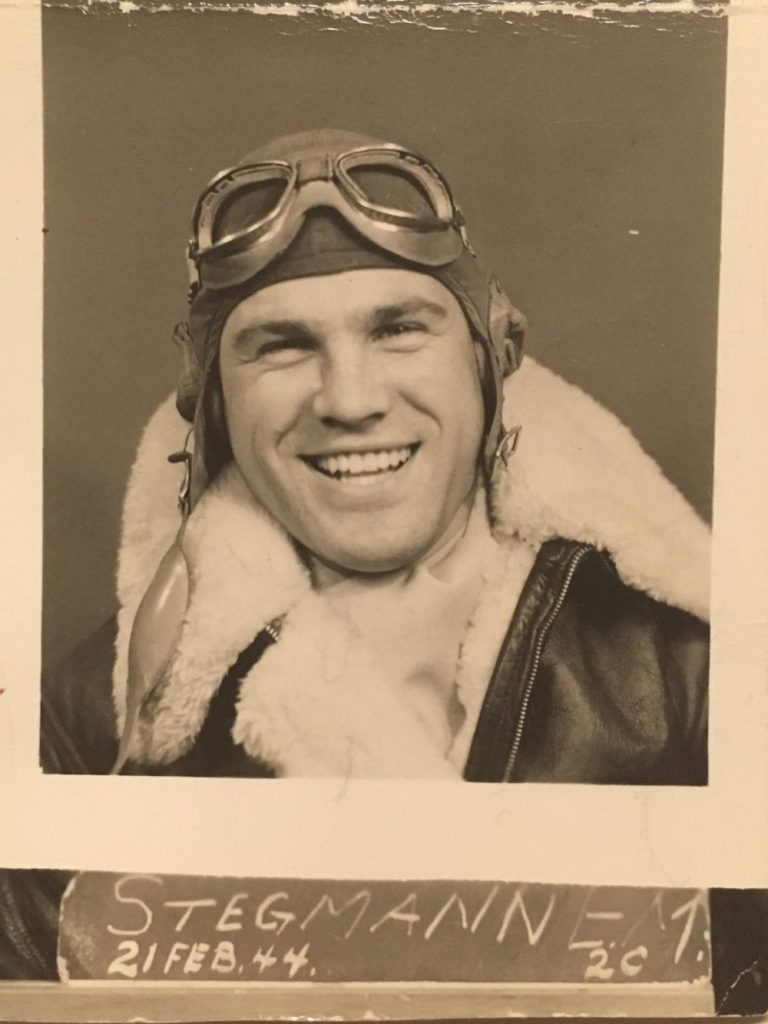

Born in Marshalltown, Iowa, on September 3, 1921, to parents Sylvester and Hazel Stegmann, Eugene Matthew Stegmann grew up in the working class as the grandson of German immigrants.

Raised during the Great Depression, he was taught an important lesson by his father: you work, or you starve. Therefore, most of his childhood was focused on working hard. Every day after school, he helped his father in their family-owned S.M Stegmann Hardware Tin Shop.

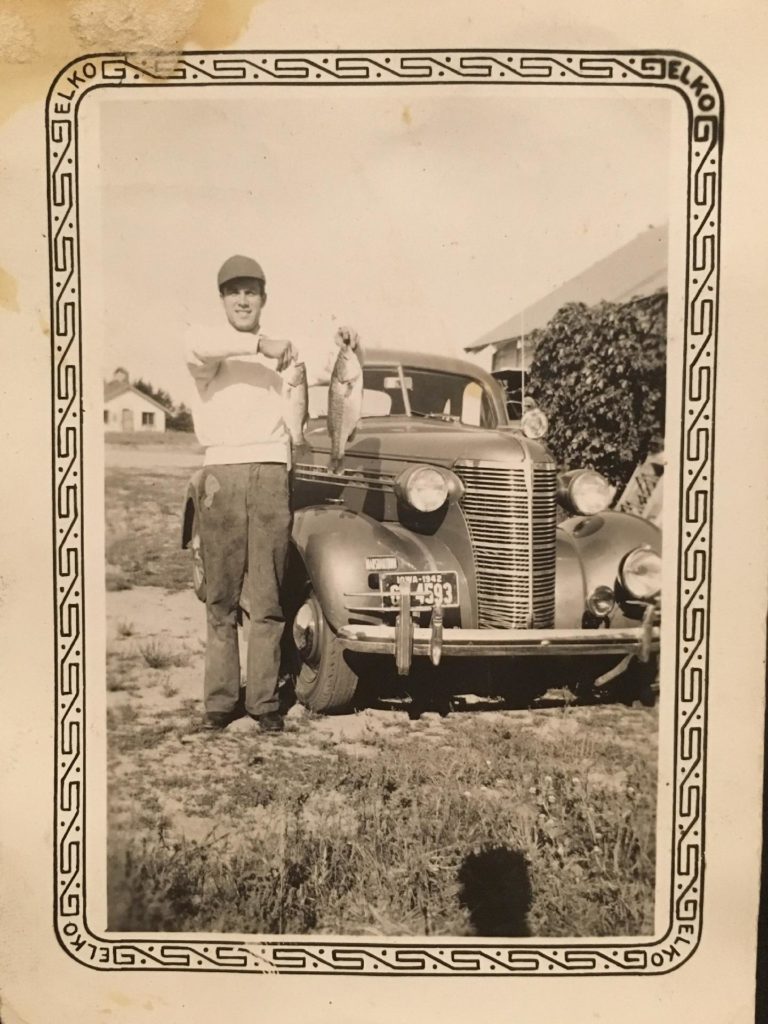

Eugene Stegmann also spent time outdoors with his younger brother, Howard. They enjoyed hunting and fishing. Both children dreamed of becoming commercial airline pilots. In the Midwest, small airstrips were common, and learning to fly was too. Eugene Stegmann would learn how to fly at Niederhauser Airfield, a small airstrip on the north side of Marshalltown.

In 1939, he graduated from Marshalltown High School at 17. After his graduation, he worked for his family business, but the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, changed the trajectory of his life.

Leaving for War

Ensign Stegmann swiftly enrolled as a cadet at Cornell College in Iowa for one year and then later received flight training at the University of New Mexico, where a V-5 Naval Aviation School was established.

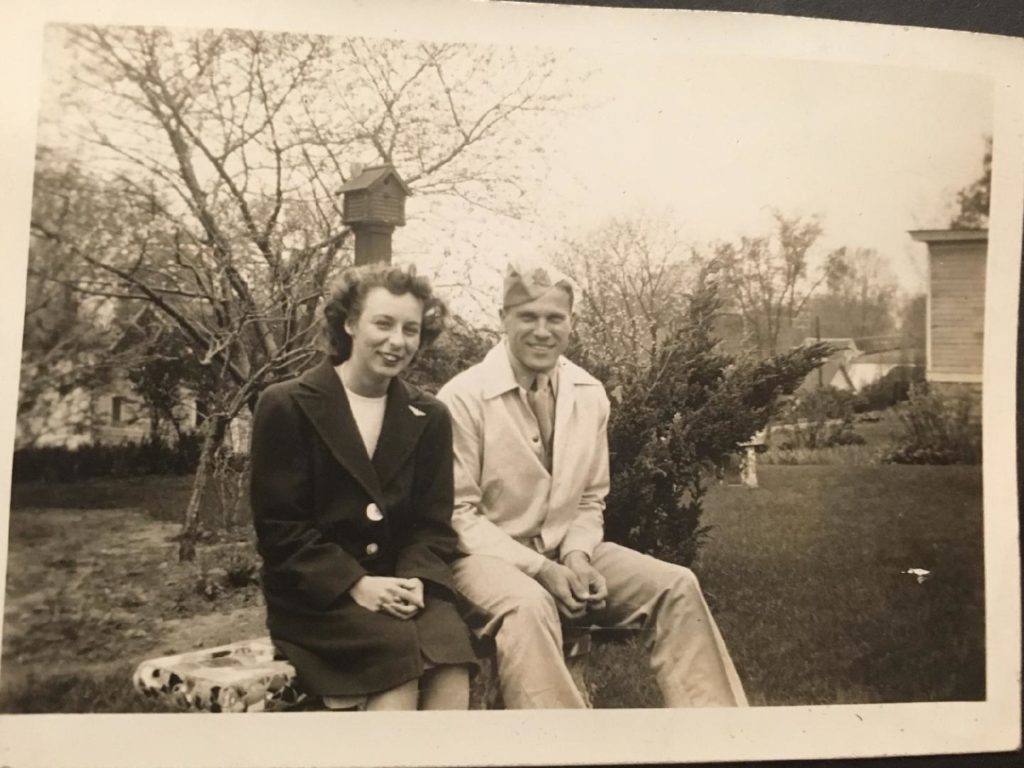

During this time, Ensign Stegmann had a girlfriend. He chose not to marry her, knowing the low survival rate of pilots and wanting to ensure that his mother could collect his life insurance. Younger brother Howard Stegmann tried to follow in his brother’s footsteps but was denied entrance into the military due to a previous injury.

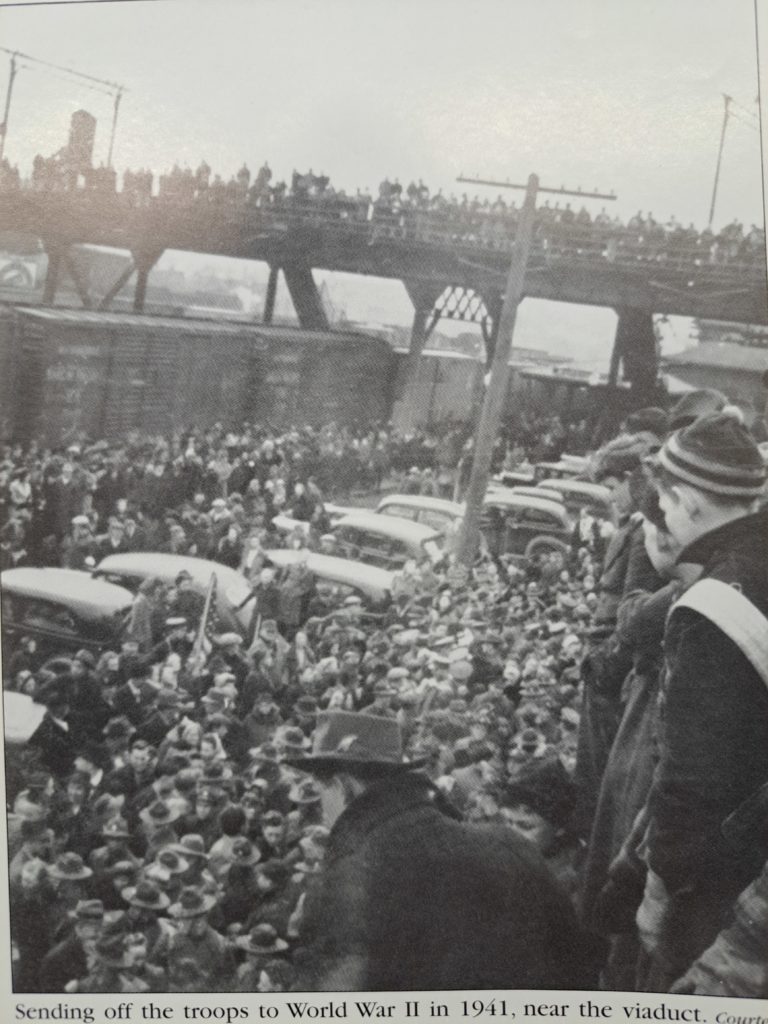

The Marshalltown community was quick to respond after the U.S. declaration of war. Located in the center of Iowa, Marshalltown was located on the transcontinental Lincoln Highway and Union Pacific rail lines, making it a key supplier of resources and supplies.

Marshall Canning Company was a major supplier of canned vegetables, and Marshall Mills packaged foods including gelatin powders, oatmeal, peanut butter, dried fruit, and coffee. Businesses such as Fisher, and Lennox would take scrap metal and send them to the war effort. Young men and women joined the war effort by enlisting in the military as soldiers and nurses, as well as becoming factory workers, suppliers, and growers of victory gardens.

Off to training

Two weeks after finishing his naval aviation training as a cadet, Ensign Stegmann formally enlisted at the U.S. Naval Reserve on February 3, 1943. In a span of two years, he was sent to five different recorded places for training including flight school in Corpus Christi, Texas, and Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. In 1945, he was sent to the Marshall Islands as a part of the Navy Scouting Squadron 66. One of the squadron’s tasks was to make daily flights over Japanese-held islands to conduct bombing and strafing runs.

Missions

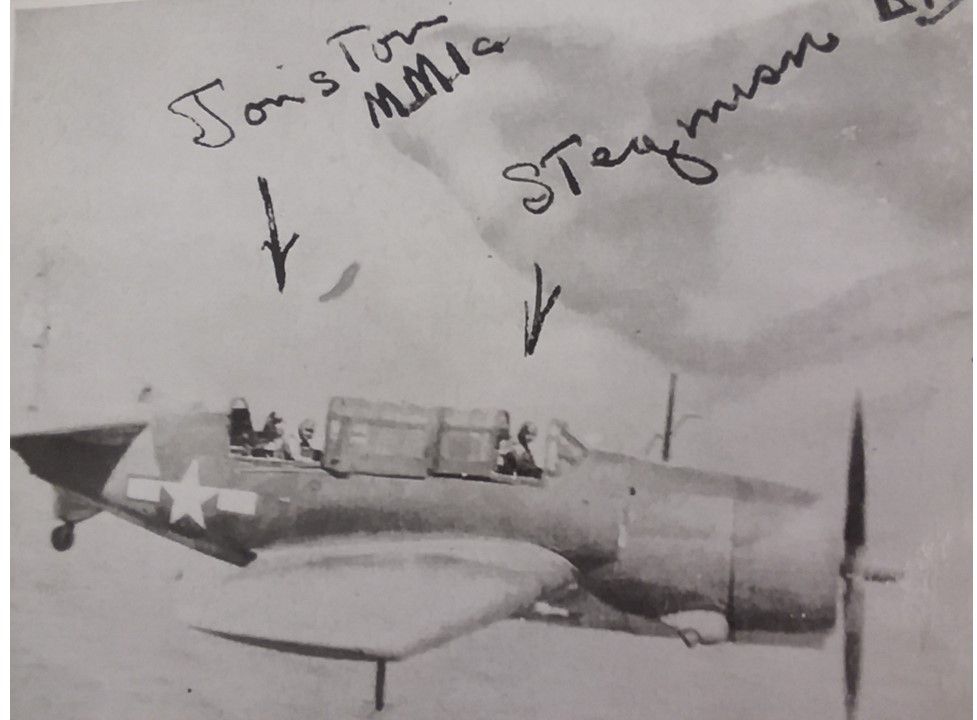

Between July 8 and 28, 1945, Ensign Stegmann completed five strafing runs using a Helldiver plane categorized as a Dive Bomber. He also participated in dropping psychological warfare leaflets over Wotje and Maloelap Atoll between July 8 and 12.

Last Flight

On the early morning of July 28, 1945, Ensign Stegmann set off in his SB2C-4 Helldiver with his gunner, Ralph Dee Fox, and another Helldiver pilot as his wingman. They flew out for their daily search of Maloelap and Wotje Atoll and made four strafing runs by 9:45 a.m.

The two planes continued on to search Mille and Jaluit Atoll, making four strafing runs and bombing the outer islands at 12:00 p.m. After the bombing, Stegmann radioed his wingman and said he would make a pass over Alu Island before going back to base. He made a tight left turn at an altitude of 300 feet. The plane began to spin out and landed upside down 150 yards away from the island. The plane immediately sank and showed no signs of survivors. Stegmann’s wingman circled the crash area for two hours waiting for a rescue ship to arrive.

Nothing was recovered.

Afterward, in a letter sent to Ensign Stegmann’s parents, Lieutenant Commander Loren C. Benny wrote on August 21, 1945, “I think it may be a satisfaction to your knowledge that Eugene was very sincere and enthusiastic about his work in this squadron, and enjoyed his life here . . . He will entirely be remembered by the fellow members of his squadron in the days of peace in which we are now entering, and which we owe to the sacrifices he and so many others have made.”

We don’t know all who gave their lives for this country, but we owe them all. We must keep the stories of their sacrifices alive. Without their stories, we forget the past and their sacrifices, and their lives are lost. Navy pilot Ensign Eugene Mattew Stegmann died on July 28, 1945, when his plane crashed near Mille Atoll of the Marshall Islands, but his story is not lost.

In a letter to Stegmann’s parents, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal stated, “Ensign Stegmann skillfully maneuvered his plane in bold defiance of frequent and intense antiaircraft fire from hostile installations and repeatedly launched his vigorous bombing and strafing attacks, inflicting serious and costly damage on Japanese-held bases in this strategic area. On each of these missions, he secured important information concerning concentrations of enemy antiaircraft positions and personnel. His heroic devotion to duty was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.” Ensign Stegmann received multiple medals, a Navy Air Medal, and a Purple Heart for his courageous service.

Ensign Eugene Matthew Stegmann, your sacrifices are not forgotten. Your story is not forgotten. And by the end of today, we will bring your story home.

Primary Sources

Aircraft Action Report (VS-66). July 16, 1945. Digital images. https://fold3.com.

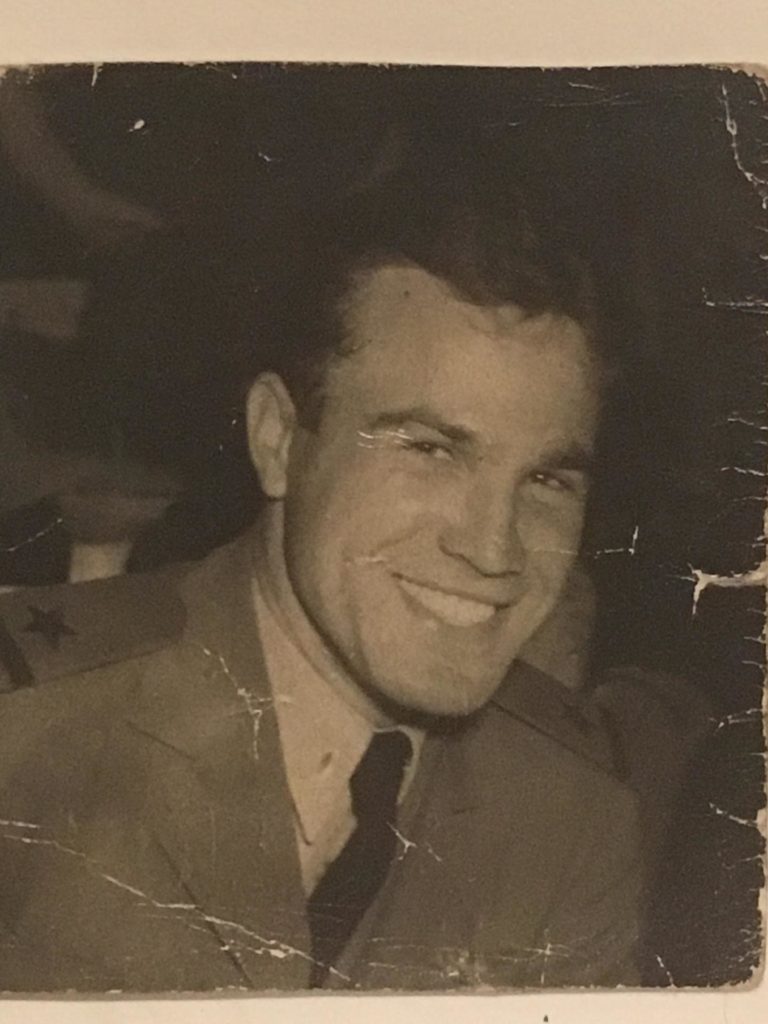

Eugene M. Stegmann. Photograph. 1939 Marshalltown High School Yearbook. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Eugene Matthew Stegmann. 1944 U.S. Navy Military Yearbook. https://ancestry.com.

Eugene Matthew Stegmann. Iowa, U.S., Births (series), 1880-1904, 1921-1944 and Delayed Births (series), 1856-1940. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Eugene Matthew Stegmann. Iowa, U.S., World War II Bonus Case Files for Beneficiaries, 1947-1959. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Eugene M. Stegmann. Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, Unaccounted-for Remains, Group B (Unrecoverable), 1941-1975. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Eugene Matthew Stegmann. U.S. Navy Casualty Books, 1776-1941. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Eugene Matthew Stegmann. World War II Draft Cards, Young Men, 1940-1947. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Eugene Matthew Stegmann. World War II Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Casualties, 1941-1945. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Forrestal, Secretary of the Navy James. Air Medal Citation for Ensign Eugene Matthews Stegmann. 1945. Stegmann Family Papers. Courtesy of Michael Stegmann.

Iowa. Marshall County. 1930 U.S. Federal Census. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Iowa. Marshall County. 1940 U.S. Federal Census. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Letter from Lieutenant Commander Loren Berry, USNR Squadron to Sylvester Stegmann. August 21, 1945. Stegmann Family Papers. Courtesy of Michael Stegmann.

Stegmann Family Photographs. Courtesy of Michael Stegmann.

Stegmann, Hazel. Stegmann Family Records. Courtesy of Michael Stegmann.

Secondary Sources

Apgar, Dorothy. The Continuing History of Marshall County: 1997. Marshalltown: History Committee of Marshall County Iowa Sesquicentennial Commission, 1999.

Apgar, Dorothy. Marshall Memories. Marshalltown: Times-Republican, 1992.

Apgar, Dorothy. Marshalltown Memories: Historic Photo Album 1853-Today.Marshalltown: Times-Republican, 1997.

“Ens Eugene Matthew Stegmann.” Find a Grave. Updated August 6, 2010. Accessed October 27, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56132537/eugene-matthew-stegmann.

“Ens Eugene Matthew Stegmann.” Find a Grave. Updated January 5, 2021. Accessed October 27, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/220704044/eugene-matthew-stegmann.

Stegmann, Mike. Personal interview. February 28, 2022.

The American Battle Monuments Commission operates and maintains 26 cemeteries and 31 federal memorials, monuments and commemorative plaques in 17 countries throughout the world, including the United States.

Since March 4, 1923, the ABMC’s sacred mission remains to honor the service, achievements, and sacrifice of more than 200,000 U.S. service members buried and memorialized at our sites.