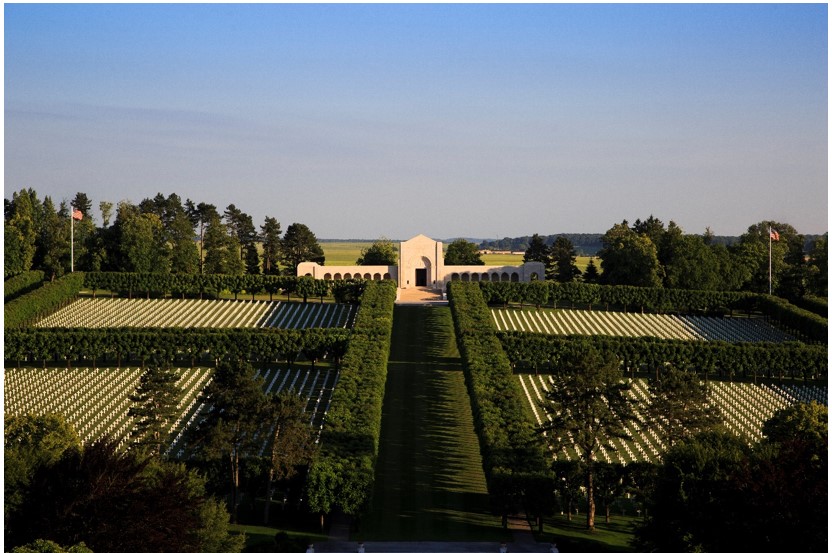

Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery is located in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, France. This World War I American Battle Monuments Commission site is the largest American Battle Monuments Commission cemetery in Europe. It contains the graves of approximately 14,300 service members. Approximately 1,000 names are also commemorated on its walls of the missing.

The first Black American recipient of the Medal of Honor in World War I

Cpl. Freddie Stowers, born Jan. 12, 1896, in Sandy Springs, South Carolina, was the eldest of six children. He worked as a farmer before marrying Pearl Watt, who was pregnant with their daughter when he was drafted into World War I. Stowers was assigned to the 371st Infantry Regiment, part of the 93rd Division.

On Sept. 28, 1918, during the attack on Hill 188, Stowers’ company led the assault. Initially, the enemy appeared to surrender, but quickly resumed fighting, resulting in intense machine gun and mortar fire. Most of Stowers’ company, including officers and commanders, were killed, leaving him in charge. Despite overwhelming odds, Stowers continued the attack. Mortally wounded, he encouraged his squad until his death, displaying extraordinary bravery.

Stowers’ actions were not formally recognized at the time. His Medal of Honor recommendation was misplaced, and his records were not revisited until 1987. In 1991, Stowers’ family was invited to the White House, where President George H.W. Bush awarded the Medal of Honor to his two surviving sisters in a ceremony. Reopening his case 70 years after his death, the government also acknowledged other forgotten black soldiers, leading to the posthumous Medal of Honor award for Pvt. Henry Johnson in 2015.

Stowers is remembered as the first African American recipient of the Medal of Honor for World War I. His grave at Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery is the most visited in the cemetery, located at Plot F, Row 36, Grave 40.

The unknown soldiers of Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and their connection to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery

Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery is the final resting place of approximately 500 unknown American service members. Among them are three who share a poignant connection with the World War I Unknown Soldier interred at Arlington National Cemetery. On Oct. 24, 1921, a solemn ceremony took place in Chalons-sur-Marne, now Châlons-en-Champagne, France, where four unidentified soldiers, exhumed from Aisne-Marne American Cemetery, Somme American Cemetery, St. Mihiel American Cemetery, and Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, were placed in identical caskets draped with the American flag.

Sgt. Edward F. Younger, a decorated veteran of World War I, was tasked with selecting the soldier. He was given a spray of white roses to place on the casket of the soldier he chose. After the ceremony, the three soldiers who were not selected were transported to Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and reburied side by side in Plot G, Row 1, Graves 1, 2 and 3.

The first American aviator to fall in World War I

Sgt. Victor E. Chapman is one of the most renowned volunteers who served prior to the official entry of the U.S. into the war.

After graduating in 1913, Chapman moved to France to study architecture. In 1914, he was in London with his father and his stepmother when they witnessed English people singing “La Marseillaise.” The scene was a revelation for Chapman who enlisted shortly after in the Foreign Legion.

Around September 1915, he was moved to an aviation unit of the French Air Service, and he started flying aeroplanes. In early 1916, the American Escadrille, later renamed Lafayette Escadrille, was formed. Chapman soon joined it.

In June 1916, the battle of Verdun had already been raging for four months, and the fighting kept intensifying. On June 23, 1916, although recovering from a head wound, Chapman departed to fly some oranges to a badly wounded friend. While in flight he saw his comrades going on patrol northeast of Douaumont and joined them. While they were slowly retreating, Chapman kept attacking the enemy who brought his aircraft down. He is the first U.S. aviator to die in combat. He is buried at Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in Plot D, Row 01, Grave 33.

The engraving robot

Since its installation in 2007 at Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, an engraving robot has significantly increased the productivity and precision of the headstone engraving process.

The robot’s setup includes four engraving tables arranged around the robot. This configuration allows the engraving of headstones in succession, such as the Latin cross or Star of David, which can be completed in about 30 to 40 minutes per headstone. Thanks to the continuous evolution of software designed to meet American Battle Monuments Commission specific needs, this machine successfully creates approximately 63% to 65% of the agency’s engraving requests across its European and Pacific cemeteries.

Adrien Remond, the site robot operator, supervises the engraving process for Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery as well as 12 other sites: Brookwood American Cemetery and St. Mihiel American Cemetery for World War I sites, as well as Ardennes American Cemetery, Cambridge American Cemetery, Epinal American Cemetery, Florence American Cemetery, Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery, Lorraine American Cemetery, Luxembourg American Cemetery, Manila American Cemetery, Netherlands American Cemetery and Rhone American Cemetery for World War II sites. In 2024, Remond engraved approximately 345 headstones. Another engraving robot is available at Oise-Aisne American Cemetery.

Remond is also responsible for the headstones from their arrival to their shipment to the other cemeteries. This includes managing the transportation logistics, which may involve road, sea or air transport for Manila American Cemetery, for instance. Furthermore, Remond is tasked with the maintenance of row markers and the proper care of Medal of Honor graves.

The flagpoles

At Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, two flagpoles stand on each side of the chapel, facing the plots where the service members forever rest. To our visitors, these flagpoles are identical. However, this is not the case.

Designed in 1930 by the architectural firm York & Sawyer, who were also responsible for the chapel’s design, these flagpoles are examples of neoclassical style. Their decorative bronze bases include many motifs, such as Roman armor, swords, axes, shields, festoons and ribbons. Atop each pole stands a bronze eagle with outstretched wings. Each flagpole is placed on an octagonal stone base, situated at the center of a circular terrace.

They were designed to create focal points that guide the viewer’s gaze along the secondary axes between the grave sections. Because the ground is not level, the two flagpoles are different in height. To make sure the two bronze eagles on top are at the same level, the flagpole on the east side is 26 meters tall, while the one on the west side is 2 meters taller making it 28 meters tall.

The American Battle Monuments Commission’s mission is to honor the service of the U.S. armed forces by creating and maintaining memorial sites, offering commemorative services, and facilitating the education of their legacy to future generations. It was founded in 1923 following World War I, and its 26 cemeteries and 31 monuments honor the service men and women who fought and perished during World War I, World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War, as well as some who fought during the Mexican American War.

The American Battle Monuments Commission sites are a constant reminder of Gen. John J. Pershing’s promise that, “time will not dim the glory of their deeds.”

Sources:

Article created with Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery’s team.

“Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era,” p.350. Williams, Chad L. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

“World War I Battlefield Companion,” Willing Patriots, p.5, American Battle Monuments Commission. Osprey, 2019.

ABMC and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (2021-09)_1.pdf

“Victor Chapman’s Letters from France,” Victor Chapman, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1917.

“The Lafayette Flying Corps, The American Volunteers in the French Air Service in World War One,” Gordon, Dennis. Schiffer Military History, Atglen, 2000.

“Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery Construction Plans,” York and Sawyer, Architects, New York, October 1930.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.